By Erika Gress, Field Scientist, Madagascar

One of nature’s most unusual, mysterious and least witnessed events happens in the ocean; coral spawning. Despite years of data collection and night snorkelling trips, for the BV Madagascar team, this rare sight has proven to be elusive.

For coral reefs and me it was love at first sight, so I didn’t think twice about trading a few nights of sleep for the chance of witnessing such a rare and magical event.

Watching and waiting for the corals to spawn

But how do we know when to anticipate the corals in Andavadoaka to spawn? Previous field scientists began researching the phenomenon in 2008 and more work was done in 2012. Spawning was documented (28-29 November 2008 and 5-6 October 2012) but sadly not witnessed due to unfavourable weather conditions. We used their research as a starting point, along with a number of published studies, and direct reproductive condition assessment of Acropora colonies when we were diving. From this we set out a predicted timetable of potential spawning events. In mid-August, 19 colonies of Acropora were tagged in one of the dive sites we survey regularly with the help of a team of our volunteers.

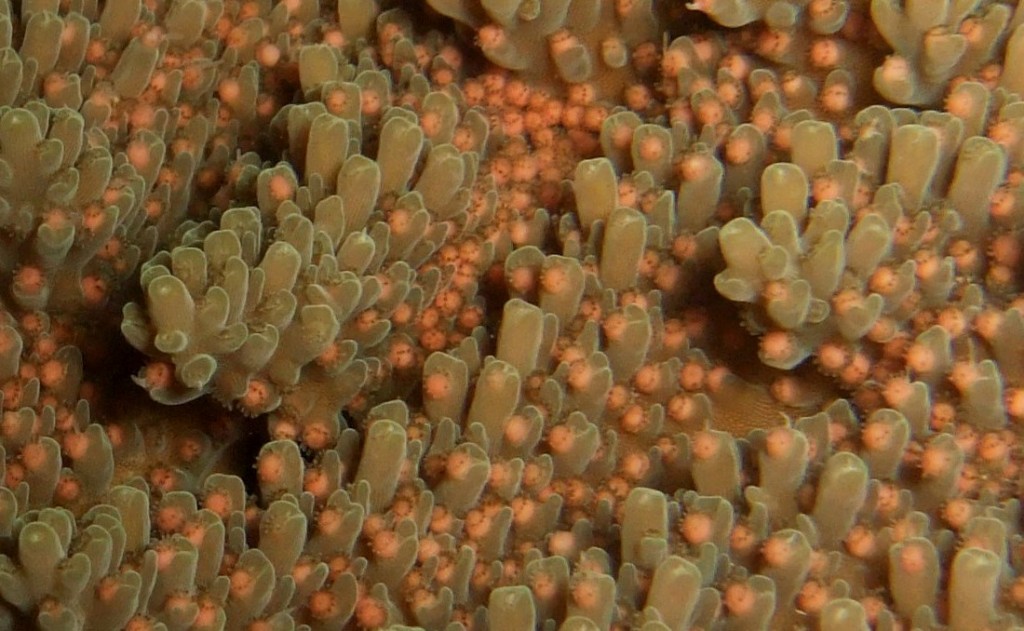

The tiny coral eggs

Acropora is one of the only two genera in which eggs are visible to the naked eye, and in most cases the presence of gametes, their colour and size gives you an idea of their maturity and thus how close they are to spawning .

After following the maturation process of the eggs, studying information from other locations where more data about spawning events is available, and taking into consideration a number of local conditions such as tides, the phase of the moon, night and day length, water temperature, etc. we began nightly snorkelling trips on the 9th of September.

Erika with the important collected samples

Sampling on a nightly basis not only increases your chances of observing a spawning event but also, through observing a sudden absence of eggs, can indicate the night of spawning in the unfortunate event that we missed it. Studies suggest most species spawn between dusk and midnight, so we dutifully arrived at our tagged colonies just before 9pm and split into buddy pairs to duck dive and observe the corals. I happily volunteered to jump in first, accompanied by Patty, a local fisher who’s been assisting our research over the past year. We jokingly informed our Dive Managers, Bill Thomson and Lisa Crews, who were waiting on the boat, that the code for spawning would be ‘It’s happeninggggggg!!’. In truth we had very little anticipation that we would actually get lucky on our first attempt.

At 21:21 Patty popped out of the water and said “come, I want to show you something“, we plunged down and I saw it; a few colonies were spawning. Words can’t describe the excitement I was experiencing. Bill and Lisa thought I was joking when I emerged exclaiming “It’s happeninggggg!!!” but soon enough they were in the water and saw it for themselves. Breath-taking!

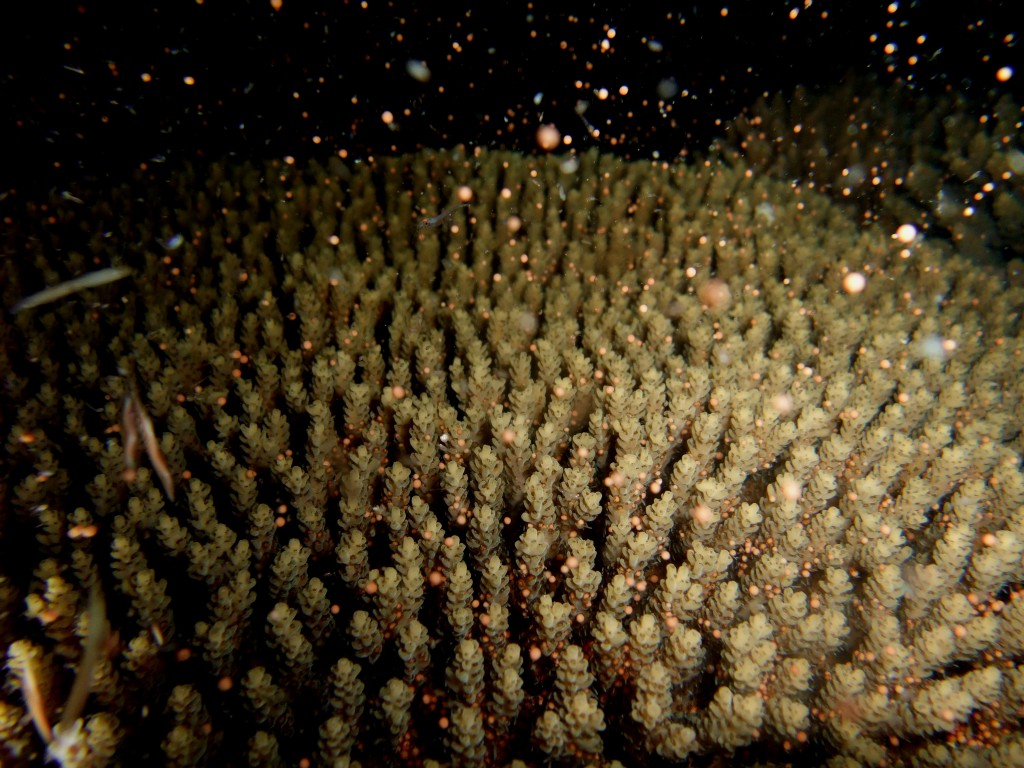

The coral starting to spawn

And as if that wasn’t enough, the event was set to a soundtrack of humpback whales singing in the water, at the tail end of their annual migration through the Mozambique Channel. We had achieved marine scientist nirvana!

We noticed that not all of the colonies we had tagged that night were spawning, and return trips confirmed that some colonies were still undergoing gametogenesis (egg production), with more, bigger and more colourful eggs. After a couple of unfruitful follow-up trips with volunteer teams, Patty, Gui (another local fisher turned research assistant), and I headed back to the reef on the night of September 25th, six days after the full moon. It was one of the darkest nights I have ever been in the water, and the bioluminescence from the wake of the boat’s propeller produced a mesmerising light display as we scooted across the ocean surface. We noticed after our first duck dives that there was an unusual amount of fish, of all sizes and we could smell their salty tang from the surface!

The setting – eggs and sperm resting under the coral’s tentacles prior to spawning

At 21:19 we observed what it is called ‘the setting’, when the eggs and sperm come to rest under the polyp’s tentacles just before they are about to spawn. We saw this in many different colonies before the mass coral spawning event began. Thousands of colonies, all releasing big pink/orange gametes into the water at the same time, explained the swarms of fish which had come to enjoy the feast; so many things going on all at the same time, it was an assault on the senses. Patty and I were trying to control our heartbeats in order to get a few good videos and pictures.

I have so often wished I had gills, but that night they would have been particularly useful.

Back on the boat, before heading back home we noticed the orange cloud that millions of eggs create at the surface of the water. That night, September 25th at around 21:25, the Mass Spawning Event was observed and recorded in situ for what we think might be the first time ever in Madagascar.

The coral is spawning!

But the fun doesn’t end there. We still have a lot of data analysis to do which we hope to turn into a publication, contributing to the pool of knowledge on this topic. Beyond the realm of academia, the most important thing is that, as we understand more about spawning, we share this knowledge with fishing communities, who depend on these reefs for their survival. We’ll present what we learned here with members of Velondriake, a local fishers association which has established a 670km² locally-managed marine area, including the reefs where we witnessed this spawning.

Let’s wish those baby corals a very very very long life!

A Madagascar first – the potential birth of a new coral reef